Clinical Trial Named Support Involving 1,300 Premature Babies

Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate the adequacy and feasibility of spoon feeding in terms of physical growth and transition to breast feeding in early hospital-discharged low birth weight (LBW) neonates.

Study Design:

A trial with two independent randomized controlled trials (RCTs), which was conducted at the tertiary-level neonatal unit of a teaching hospital and included home-based treatment. Singleton alive-born neonates with a gestational age of ⩾32 weeks, a birth weight of >1250 thousand and ⩽1600 grand, and fulfilling the feeding criteria were included in the study. The written report was conducted over an 18-month period with 79 and 65 subjects enrolled into two RCTs in a large trial. Weight proceeds pattern during the study period was the primary outcome variable, and the number of days required by the neonate for transition to breast feeding and feeding-associated morbidity were the secondary variables. In Trial I, babies were gradually transitioned from nasogastric (NG) feeding and spoon feeding to breast feeding in the infirmary, whereas in Trial II, babies were transitioned from spoon feeding to breast feeding in the infirmary and at home. Eligible neonates were randomized into one of the two groups in each of the two trials using a estimator-generated random number sequence. Trial I consisted of NG feeding and spoon feeding groups, both in a hospital setup, whereas Trial 2 consisted of a spoon-feeding grouping in infirmary and abode setups.

Result:

Baseline neonatal and maternal characteristics were comparable in both groups of each trial, including maternal medical and obstetrical morbidities. In Trial I, out of 79 babies enrolled, 72 babies (91.1%) completed the study, whereas in Trial II, 92.iii% (60 babies out of 65 babies enrolled) neonates completed the trial. The mean (s.d.) weight proceeds in neonates during the study menstruation in Trial I in a infirmary setup was 4.72 (4.68) 1000 kg−1 per day in the NG feeding group and 4.47 (iii.14) g kg−1 per day in the spoon-feeding grouping (P=0.8836). Similarly, spoon-fed babies gained 7.06 (4.26) g kg−1 per day in the hospital group, whereas they gained 7.56 (3.31) 1000 kg−ane per day in the home group (P=0.5984) during the study period of 28 days. Afterwards randomization, the time taken for transition to breast feeding was 12.31 (three.32) days and 14.39 (four.x) days (P=0.0201) in Trial I, whereas information technology was three.55 days and 9.81 days (P=0.0000) in Trial II in the 2 groups, respectively. In Trial 2, the hateful (s.d.) duration of infirmary stay was xiv.58 (two.83) days in the hospital group and 10.19 (ii.26) days in the dwelling house grouping (P=0.0000). Neonatal morbidity was comparable during the study catamenia in the two groups in both trials.

Conclusion:

Use of supplementary spoon feeding is establish to be adequate and feasible in terms of physical growth and transition to breast feeding in early hospital-discharged (dwelling house grouping) LBW babies.

Introduction

The nutritional direction of very low nascence weight (VLBW) infants has a major function in their immediate survival and subsequent growth and developmentone. To offset with, nasogastric (NG) feeding of expressed breast milk (EBM), along with nonnutritive sucking (NNS), is a standard method for neonates with a gestational age of ⩾32 weeks and a nascence weight of >1250 g and ⩽1600 one thousand.ii Later, these babies are transitioned to chest feeding before being discharged domicile. Because of the express use of gavage feeding and disadvantages of bottle feeding, alternative feeding methods such as loving cup feeding/paladai feeding have been tried in before studies.2, 3, 4, v, six In northern India, along with breast feeding, spoon feeding of remaining EBM is an additional method of infant feeding that has been prevalent in society for a long time. This is also a standard practice of feeding LBW newborns built-in in the neonatal unit of measurement of our infirmary since more than a decade, without its objective evaluation.

Traditionally, weight continues to be major discharge criteria of LBW infants,7, 8, 9 and it is believed that discharge from hospital at a low weight is chancy.10 Notwithstanding, subsequent studiesvii, 11, 12, 13, 14 hold with regard to certain behavioral criteria needed to be achieved before hospital belch of premature infants. Therefore, at that place has been a need-felt requirement for exploring additional feeding methods earlier transition to breast feeding to meet the optimal nutritional requirement of these babies both in the hospital and at domicile.

This study attempts to evaluate the contribution of the spoon-feeding method in the nutritional direction of LBW babies both in the hospital and at home. If spoon feeding is adequate and feasible in terms of physical growth and transition to breast feeding at home, information technology tin can effect in an early on hospital belch of LBW neonates.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the adequacy and feasibility of spoon feeding in terms of concrete growth and transition to breast feeding in early infirmary-discharged LBW neonates.

Methods

Written report design

A trial with two contained randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Setting

A tertiary level neonatal unit of measurement of a teaching hospital and habitation-based treatment.

Subjects

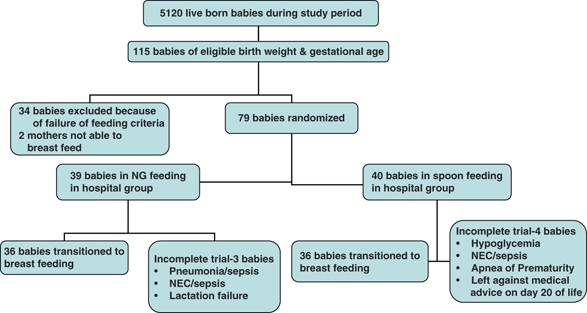

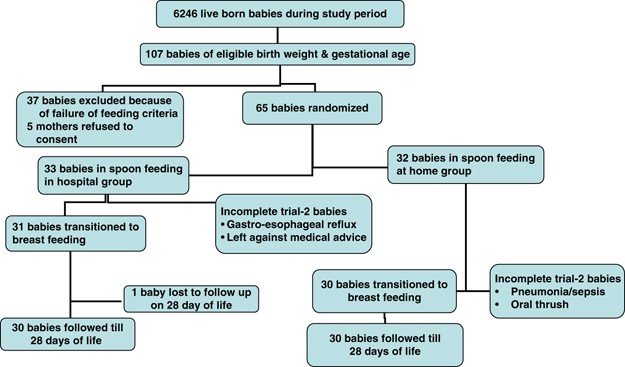

Singleton live-built-in neonates with a gestational age of ⩾32 weeks, with a birth weight >1250 g and ⩽1600 g and fulfilling feeding criteria. The written report was conducted over an 18-calendar month flow with 79 subjects enrolled in Trial I (Effigy one) and another sample of 65 subjects enrolled in Trial II (Figure 2).

Flow chart for the random allotment of NG feeding and spoon-feeding neonates in a hospital setup and their transition to breast feeding in Trial I.

Flow nautical chart for the random allotment of spoon-feeding neonates in the hospital and at home, their transition to chest feeding and 28 days follow-up in Trial Ii.

Inclusion criteria

All singleton live-born neonates delivered at the obstetric unit of measurement of the hospital to mothers residing in Delhi with a gestational age of ⩾32 weeks, with a birth weight >1250 thou and ⩽1600 g and fulfilling feeding criteria were included in the study. In Trial I, babies receiving ⩾30 ml kg−ane per day of enteral feeds by the NG route for ⩾12 h, and thereafter accepting one spoon feed, fulfilled the feeding criteria (age ⩽5 days). In Trial 2, babies on chest feeding, and the remaining EBM by spoon feeding, and having constant/gaining weight ⩾48 h fulfilled the feeding criteria (weight ⩾1300 one thousand and age ⩽14 days).

Exclusion criteria

Neonates were excluded if they had major congenital malformations, hypotonia, intracranial hemorrhage, meningitis or encephalopathy and so on requiring an alteration in their feeding schedule.

Outcome variables

Primary: The primary outcome of the report was the weight gain pattern during transition to breast feeding in hospital in Trial I, whereas in Trial 2 babies, the primary outcome of the study was weight proceeds pattern till 4 weeks of age. Secondary: The secondary result variables included the number of days required by the neonate for transition to breast feeding and spoon feeding-associated morbidity.

Randomization

Eligible neonates were randomized to 1 of the two groups using computer-generated random number sequence placed in opaque sealed envelopes—NG feeding and spoon feeding in infirmary (Trial I), and spoon feeding in hospital and at dwelling house groups (Trial Two).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from either of the parents in both trials. Both trial protocols were approved past the Institutional Ethical Committee.

Sample size

To analyze a departure in weight gain of 5 g kg−1 per day in neonates in the two groups, with an α fault of 0.05 and a power of report of 80%, it was estimated that a sample size of 30 neonates in each group were required.

Intervention

Standard plant nursery protocol was used for feeding eligible neonates. Neonates were started and continued on NNS every bit soon as their clinical condition stabilized, before randomization and during the trial, till they were transitioned to chest feeding. Feeds were initiated at sixty ml kg−1 per day divided into equal 2-hourly feeds, with an increase of 30 ml kg−ane per day and maximum feeds of 180 ml kg−ane per day. The milk used was from the biological mother only every bit far every bit possible. It was collected after expressing out maximum possible milk from both breasts. The milk was mixed thoroughly and the desired book was collected in a make clean bowl using a plastic syringe. If EBM was insufficient, it was supplemented with Delhi Milk Scheme milk. NG feeds were given by the staff nurse only. To start with, spoon feeds were given by the staff nurse. After, mothers were trained in spoon feeding, who and then fed the babies. The metallic spoons used had a chapters of two to 3 ml with polish edges and then as not to crusade trauma to the neonates. The baby was held in an upright inclined position comfortably on the lap. The spoon was at to the lowest degree half-filled with milk and was offered to the infant such that the rim of the spoon was directed towards the lip and gums, resting on the lower lip with the milk line touching the upper lip. The spoon was then held in this position and the babe was allowed to consume every bit much milk as needed by lapping and/or sipping. The spoon was sterilized in a boiler, dried and reused. During spoon feeding, the amount of milk consumed and the corporeality of milk spilled were noted. Feed intolerance was defined as an increase in abdominal girth >ii cm from the previous recording and gastric aspirate >20% of the previous feed. After 24 h of bowel residuum, feeds were restarted using the same method at ¼, ½, ¾, and total charge per unit on subsequent days, of the volume at which feeds were stopped.

Trial I

In babies randomized to the NG feeding group, NG feeds were gradually replaced and, depending on tolerance, babies were transitioned to exclusive breast feeding. In babies randomized to the spoon-feeding grouping, spoon feeds were replaced gradually and, depending on their tolerance, were transitioned to chest feeding as early on as possible. During this period, the remaining volume of the required feed not accepted past spoon was provided through the NG route. The criteria of tolerance used were no feed intolerance along with no weight loss in the last 12 to 24 h.

Trial Ii

A like feeding protocol as that mentioned in babies belonging to the spoon feeding in hospital grouping in Trial I was followed till neonates were transitioned to chest feeding, followed by remaining EBM by spoon feeding. At this stage, babies were randomized to either of the two groups. Neonates randomized to the spoon feeding in hospital grouping were transitioned to breast feeding in hospital and discharged on exclusive breast feeding with constant/gaining weight for ⩾48 h. Neonates randomized to the grouping with spoon feeding at home were discharged on the same day of randomization and were transitioned to exclusive breast feeding at home. All mothers were advised to bring the neonates twice a week for feeding evaluation, anthropometric measurements and morbidity if any, till 4 weeks of age. For this purpose, specially designed performa was given to mothers to record the number of feeds given to the babe past breast feeding or spoon feeding or both, as well every bit the volume of milk. In case the mother failed to written report to the newborn nursery on her scheduled visit, efforts were made to contact her by phone (same mean solar day/subsequent day) and by home visit.

Statistical analysis

All information obtained were entered into a computer using EPI INFO VERSION 6. An intention-to-treat analysis approach was used to analyze data. A P-value of <0.05 was considered every bit significant. Usually distributed continuous data were analyzed using the ANOVA examination. Bartlett'south test was used for evaluating the homogeneity of variance. The Mann–Whitney or Wilcoxon's two-sample test (Kruskel–Wallis H-examination for 2 groups) was used for nonparametric information. Graphs were prepared using Microsoft Excel.

Enrollment of subjects

In Trial I, during the study period of viii months, a total of 5120 singleton live-born babies were delivered (Figure 1), of whom 79 neonates were enrolled into the study. Similarly, in Trial 2, during the enrollment catamenia of ix months, a total of 6246 singleton live-born babies were delivered (Figure 2), of whom 65 babies were enrolled into the study.

Results

Baseline neonatal and maternal characteristics

Table 1 shows baseline neonatal characteristics in the ii trials. The characteristics of babies were comparable with regard to gestational age, weight, length and head circumference at nativity, ponderal index, small for gestation age, sex, mode of delivery, evidence of perinatal asphyxia (fetal distress and APGAR scores) and resuscitation required. Trial I had a comparable number (%) of preterm and VLBW babies in the two groups [36 of 39 (92.three) vs 35 of forty (87.v) and 27 of 39 (69.2) vs 27 of twoscore (67.5), respectively]. Furthermore, the number (%) of preterm babies in the spoon feeding in infirmary group and the number in the spoon feeding at home grouping were besides comparable [26 of 33 (78.8) and 24 of 32 (75), respectively] in Trial 2, besides as the number (%) of VLBW babies [fifteen of 33 (45.5) and 12 of 32 (37.5)] in the two groups. Mothers of babies in both groups of each trial were comparable (Table 2) with respect to historic period, parity, educational activity and socioeconomic status.15 Pregnancy was booked in a comparable number of mothers in both groups of each trial. Both medical (anemia, jaundice, tuberculosis, rheumatic middle affliction, syphilis) and obstetrical (APH, PIH, preeclampsia, eclampsia, oligohydramnios) maternal morbidities were also comparable in the two groups of each trial.

Compliance

In Trial I, out of 79 babies enrolled, 72 (91.1%) were transitioned to breast feeding (Figure 1), whereas in Trial II, out of 65 babies enrolled, 61 (93.8%) could be transitioned to breast feeding, of whom 60 babies (92.3%) were followed up till 28 days of age (Figure two).

Weight gain pattern during the study menses

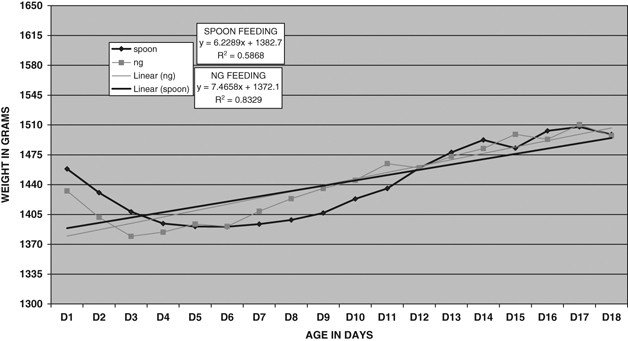

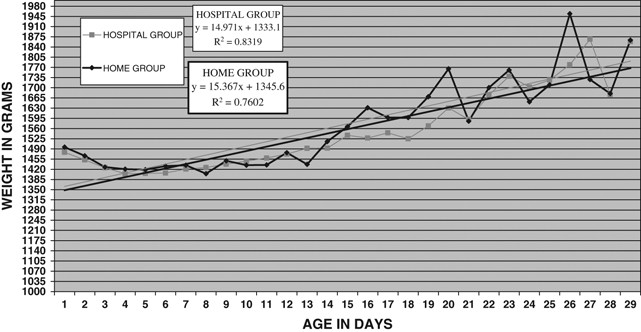

In Trial I, Figure 3 shows daily weight changes in the two study groups. The mean (s.d.) weight at birth in both groups was comparable (Table three). Moreover, babies were enrolled in the study at a comparable age—3.36 (ane.67) days in the NG feeding group vs iii.30 (1.24) days in the spoon-feeding group (P=0.8586). Finally, at the upshot age of xv.64 days in the NG feeding group vs 17.67 days in the spoon-feeding group, babies in the 2 groups had a weight of 1543.75 (120.42) g vs 1578.47 (95.30) thousand, respectively (P=0.1793)). The mean (s.d.) weight gain was iv.72 (4.68) one thousand kg−i per twenty-four hour period in the NG feeding in hospital grouping and 4.47 (3.xiv) g kg−one per day in the spoon feeding in hospital grouping (P=0.8836) from nascency till transition to breast feeding. In Trial II, Figure 4 shows daily weight changes in the two report groups. The hateful (southward.d.) weight at birth in the spoon feeding in hospital and spoon feeding at home groups was comparable (Table three). Babies were enrolled into the study at a comparable historic period [xi.06 (2.42) days and x.19 (2.46) days, P=0.155], and received comparable feeds [137.iii (29.6) ml kg−1 per twenty-four hour period and 128.viii (25.vii) ml kg−ane per solar day, P=0.2217] in the spoon feeding in hospital and spoon feeding at dwelling house groups, respectively. Finally, at a comparable outcome age [27.iv (iv.09) days and 28.0 (2.63) days, P=0.4587], babies belonging to the spoon feeding in hospital group and spoon feeding at habitation group had no significant difference in weight [1827.88 (213.9) thousand and 1859.22 (219.9) g, respectively P=0.5623]. Babies gained a weight of 7.06 (4.26) chiliad kg−i per day [206.00 (111.36) g kg−1] in the spoon feeding in hospital group and 7.56 (3.31) g kg−ane per twenty-four hours [211.47 (94.26) g kg−ane] in the spoon feeding at domicile group (P=0.5984) during the entire study menstruum, that is, from birth till 4 weeks of postnatal age, resulting in an boilerplate of 5.47 yard kg−ane (ane.37 1000 kg−1 per calendar week) more weight gain over four weeks in babies in the spoon feeding at home group compared with babies in the spoon feeding in hospital group. The weight loss/gain later birth at weekly intervals till iv weeks of age also did not differ significantly in the two groups.

Line diagrams showing mean weights for historic period in days along with linear regression lines in NG feeding and spoon-feeding neonates in a hospital setup in Trial I.

Line diagrams showing mean weights for age in days along with linear regression lines in spoon-feeding neonates in the infirmary and at home in Trial 2.

Time flow for transition to breast feeding

In Trial I, during the entire study period, babies belonging to both NG and spoon-feeding groups received a comparable number (s.d.) of NNS per twenty-four hour period [half dozen.11 (i.53) vs half-dozen.75 (i.34), P=0.4420, respectively]. The mean age at randomization in both groups was comparable (Table iv). The time (s.d.) taken for transition to chest feeding in the NG feeding grouping was 12.31 (3.32) days, whereas in the spoon-feeding group it was 14.39 (four.x) days with a P-value of 0.0201. In Trial 2, the mean (s.d.) age at randomization was comparable in the two study groups (Table iv). However, the mean (s.d.) historic period at transition to breast feeding was significantly different (P=0.0017), resulting in a significant departure in the time interval required between randomization and transition to breast feeding [three.55 (1.09) days vs 9.81 (3.16) days, respectively, P=0.0000] and weight at transition to chest feeding [1546.9 (92.69) m in spoon feeding in infirmary and 1680.0 (175.54) g in the spoon feeding at home groups (P=0.0004)]. During the period of transition, babies received a comparable number of chest feeds per day, merely the hateful (southward.d.) number of spoon feeds consumed per day [2.52 (1.eleven)] in the spoon feeding in hospital grouping was significantly lower than that of feeds in the spoon feeding at home group [six.32 (1.36), P<0.001].

Feeding-associated morbidity

In Trial I of this report, v babies developed morbidities/mortality (Figure ane). Two babies in the NG feeding grouping—one with a nativity weight of 1480 g, with a gestation age of 39 weeks (asymmetric IUGR), who was enterally fed for 3 days, died on day 7 of life because of pneumonia and sepsis (civilisation negative), whereas the other one, with a nascency weight of 1510 m, a gestation age of 32 weeks, who was enterally fed for 5 days, died on solar day 8 of life because of necrotizing enterocolitis. Three babies in the spoon-feeding group—one with a nativity weight of 1430 chiliad, a gestation age of 38 weeks (asymmetric IUGR), who was enterally fed for 1 day, adult hypoglycemia; the second babe with a nativity weight of 1335 g, a gestation age of 34 weeks (symmetrical IUGR), who was enterally fed for 5 days, adult NEC and sepsis (culture negative), whereas the third baby with a birth weight of 1590 g, a gestation age of 34 weeks, who was enterally fed for 3 days, developed apnea of prematurity. Moreover, i additional baby in the spoon-feeding group was given NG feeding for 24 h time because of oral thrush.

In Trial Ii (Figure two), afterward a randomization of the written report population of 65 babies, 4 babies (1 in the spoon feeding in infirmary grouping and 3 in the spoon feeding at home group) adult morbidities before 28 days of age. One baby in the spoon feeding in infirmary grouping with a birth weight of 1570 thou, a gestation age of 34 weeks, enrolled on day xiv of life, developed gastroesophageal reflux (GER) on mean solar day 18 of life and required intravenous fluids for five days. One infant with a birth weight of 1590 thou, a gestation age of 37 weeks (symmetric IUGR), belonging to the spoon feeding at dwelling grouping discharged on mean solar day 8 of life, was readmitted on day 11 of life with 17% weight loss and oral thrush. Oral thrush was treated and the baby was continued on chest feeding and remaining EBM by spoon feeding and was discharged later on 7 days of hospitalization upon adequate weight gain. The second baby in the same group with a birth weight of 1475 g, a gestation historic period of 34 weeks (disproportionate IUGR), discharged on day 8 of life was readmitted on twenty-four hours xv of life with sepsis, pneumonia and meningitis (culture negative) and required intravenous antibiotics for ii weeks and was discharged on 24-hour interval 28 of life. Another baby in the spoon feeding at home group with a birth weight of 1595 g and a gestation age of 38 weeks (asymmetric IUGR) adult oral thrush on the 24-hour interval of enrolment (twenty-four hour period half-dozen of life) only was discharged on the aforementioned day with local handling for oral thrush, and was able to follow the expected feeding schedule similar to other written report subjects.

Discussion

This study was conducted equally two contained RCTs. In Trial I, the aim of the study was to evaluate physical growth, especially the weight gain pattern in babies on spoon feeding under a controlled hospital environment. Once proved, information technology gave us the confidence to make an early infirmary discharge of these babies (Trial II) to evaluate the adequacy and feasibility of spoon feeding at habitation as well.

Nutrition in LBW babies—adequacy and feasibility of spoon feeding in hospital

Experience in the developing globe and in several European neonatal intensive and transitional care unitstwo indicates that cup feeding is a skill easily acquired past preterm infants at a stage (⩾32 weeks) earlier efficient breast or bottle feeding is possible, and when gastric tubes are considered a necessity. The studies evaluating loving cup feeding take establish it to be a uncomplicated, practical, noninvasive and effective method of feeding LBW babies, which encourages the interest of both parents. With cup, the feeding session is controlled by the babe by controlling the stride of licking/sucking; respiration is easier to control and swallowing occurs when the infant is ready. Equally a result, very picayune energy is required and the infant may be physiologically more stable.5 During cup feeding, tension of the natural language is forward, over the lower alveolar ridge to lap the milk into the mouth, which may assist in the subsequent development of correct breast feeding natural language movements.6 On the basis of the above feel and a marked similarity to the spoon-feeding method with loving cup/paladai, we hypothesized that instead of NG feeding, spoon feeding can exist used for transitioning LBW babies to chest feeding in the hospital with comparable physical growth. In Trial I, we demonstrated that LBW babies tin can be started on spoon feeding, along with NNS, for the subsequent transition to breast feeding with comparable weight gain and other anthropometric parameters during this menstruation. In this study, the mean weight proceeds was four.72 g kg−1 per twenty-four hour period in the NG feeding in hospital group and four.47 g kg−ane per day in the spoon feeding in hospital group (P=0.8836) during the written report period. Similarly, the mean (s.d.) gain in head circumference was 4.50 (ii.02) mm and 4.56 (ane.40) mm per week (P=0.4956) and the mean (s.d.) proceeds in length was 4.67 (ane.77) mm and 5.83 (2.50) mm per week (P=0.1542) in the two groups, respectively. The available literature on alternative feeding methods has non attempted to evaluate the weight gain pattern of babies according to whatsoever of these feeding methods. In this study, the mean age at transition to breast feeding was approximately two days longer in babies in whom the transition to breast feeding was attempted with spoon feeding in comparing with that in the NG feeding grouping (17.67 vs 15.64 days, respectively, P=0.0249). Although statistically significant, this deviation of 2 days is of limited clinical significance, especially considering other major advantages of spoon feeding (similar to advantages with cup feeding, as enumerated before).

In a study conducted by Malhotra et al.,iii it was revealed that the volume of feeds ingested was more with paladai and cup, and the time taken was significantly less when compared with bottle. In the same study, nurses were individually questioned regarding their opinion on the method of oral feeding. They were unanimous in selecting the paladai every bit the method of selection. The advantages highlighted included the ease of cleaning and sterilization of utensils used, grooming mothers and the less time involved in feeding. They as well observed that there was less exertion required on the part of infants. There were no identifiable disadvantages. Even so, in present study, the volume (s.d.) of milk consumed from nascency till transition to breast feeding was comparable, that is, 103.16 (11.39) ml kg−i per day by the NG road in the NG feeding in hospital group and 104.89 (15.53) ml kg−one per mean solar day by both spoon and NG routes in the spoon feeding in infirmary groups (volume of milk by the NG route: x.92 (13.63) ml kg−1 per solar day) (P=0.5865). Furthermore, the time taken [hateful (due south.d.)] by babies for spoon feeding was vii.89 (1.02) minutes/feed.

In Trial I, v babies had associated morbidity during the study period. Ii babies died during NG feeding in the hospital group—i with pneumonia and sepsis and the other with necrotizing enterocolitis. In the spoon feeding in hospital grouping, iii babies developed various morbidities—one with hypoglycemia, another with necrotizing enterocolitis and sepsis and the third with apnea of prematurity. Thus, spoon feeding does not seem to betrayal infants to increased morbidity/mortality.

Early hospital discharge—adequacy and feasibility of spoon feeding at habitation

Many studies7, xi, 12, 13, fourteen have demonstrated that behavioral criteria such as temperature stability out of the incubator and the ability to suck and gain weight on oral intake needs to be achieved earlier the hospital discharge of premature infants. Therefore, there has been a demand to use an additional feeding method such as spoon feeding before transition to breast feeding both in hospital and at domicile to meet the optimal nutritional requirement of these babies. In Trial 2 of this study, we tried to prove whether babies can exist discharged early from hospital, as spoon feeding tin exist continued at home during transition to breast feeding, with comparable physical growth and no increased risk of spoon feeding-associated morbidity. In Trial II, babies belonging to the spoon feeding at home grouping had a significantly shorter elapsing of infirmary stay (x.19 vs xiv.58 days, P<0.001) compared with babies belonging to the spoon feeding in hospital group with comparable weight (south.d.) gain during the entire report menstruation [11.97 (7.27) g per solar day and 12.91 (6.48) g per day, P= 0.5856, respectively]. It was considering of the fact that these LBW babies were discharged from hospital to their home at a stage when they were having constant/gaining weight on breast feeding, followed by remaining EBM by spoon feeding, rather than transitioning them in the hospital itself to breast feeding simply. Cruz et al. 12 conducted a randomized clinical trial of belch of VLBW infants at a weight of 1300 g vs 1800 g from the neonatal intensive care unit, comparing weight gain and incidence of infection. Preterm infants weighing <1300 m at birth were enrolled in the study when they achieved a weight of 1300 1000 to 1350 yard if they met the behavioral criteria for discharge and the family home was approved. The mean nascency weight and gestational age of the included infants were 1135 g vs 1160 k and 30.7 weeks vs 31.two weeks, respectively, for the two groups. Infants in the dwelling house group were discharged presently subsequently entry into the study. Those in the infirmary group were discharged at 1800 thou, following the standard protocol. The duration of hospital stay was significantly depression for the home group, that is, 23.five±8.five days vs 42.5±ten.9 days. The mean weight gain was 32.7 chiliad per solar day in the dwelling group equally compared with 32.1 g per solar day in the infirmary grouping in babies with a gestation age of 36 to 40 weeks. Two infants in the home group (n=27) were readmitted after 7 days of belch from hospital. Ane had diarrhea and the other had pneumonia (both culture negative). Klebseilla aerobacter meningitis adult in one baby in the hospital grouping after 7 days of enrollment into the written report. No infant died during the report period. Using behavioral criteria, the weight at discharge for the study grouping in this report at 1300 to 1350 k was considerably less than that in previous reports. The cost of providing additional follow-upward intendance was a pocket-sized percentage of infirmary toll and the result was a big net saving. The success of this written report can be partially explained by the preponderance of SGA infants (51%) who are relatively mature at LBWs, which emphasizes the importance of maturity rather than size for defining belch criteria. Gibson et al. xiii conducted a study in which infants of birth weight ⩽1800 thousand and a gestational age <36 weeks were randomized to an accelerated or conventional group when they were clinically stable. The accelerated group averaged 12.6 days less hospital stay than did the conventional group (33.2 vs 45.8 days) and 7.3 days more of home care (17.2 vs 9.ix days, for an overall net of five.3 days less of supervised (hospital plus domicile) care. The report reported a mean weight gain of 24.3 g per solar day and 28.seven g per twenty-four hour period for conventional and accelerated discharge groups, respectively, for babies in the weight range of 1800 to 2000 g. A shorter duration of hospital stay (range, half dozen.vii to 19.5 days) has too been reported by other published studies7, 11, 14 for babies discharged according to behavioral criteria as compared with standard criteria of preset weight. As bulk of LBW babies after birth take physiological weight loss for a variable flow of time, it could account for the lower weight proceeds over 4 weeks of time in present report in comparison with weight proceeds as reported by Cruz et al. 12 and Gibson et al. 13 Despite providing a written performa and feeding advice at discharge, the mothers of babies belonging to the spoon feeding at home group continued to spoon feed the babies at home for a longer elapsing [mean (s.d.) 9.81 (three.51) vs 3.55 (one.89) days, respectively, P<0.001], probably to ensure that babies become maximum breast milk. The available literature has not evaluated whatever of the additional feeding methods at home.

Iii babies adult morbidities. One baby who received spoon feeding for 10 days (7 days in hospital and 3 days at home) was readmitted on the 11th day of life with oral thrush. Another baby receiving spoon feeding since birth developed oral thrush on the sixth day of life and was discharged domicile on the same day with local treatment for oral thrush. Some other baby who received spoon feeding for eight days in hospital and 7 days at home adult sepsis along with pneumonia and meningitis (blood civilisation negative) on the 15th day of life. The role of spoon feeding-related hygiene resulting in morbidity in these three babies was hard to evaluate. Furthermore, the contribution of surroundings either in the hospital or at home in the causation of feeding method-related infection or otherwise could not be defined. However, the possible association of infection, if any, can be minimized by proper maternal education regarding feeding hygiene. In this study, the provision for routine follow-up home visits providing health care was not available. The reason for not providing routine home visits was the very high follow-up rate of babies to the plant nursery as observed over the past several years. Home visit was planned only when mothers failed to study to nursery on their scheduled visit, fifty-fifty after phone contacts.

Therefore, it can be concluded that early hospital discharge (4.39 days in this study) of babies with a gestation age of 34 to 35 weeks and a birth weight of 1450 to 1500 g, especially pocket-size for the gestation age (one-half to 2-thirds in this study), is feasible with comparable physical growth using the spoon-feeding method both in the hospital and at domicile for transitioning to breast feeding, provided the female parent is educated in proper spoon feeding hygiene. The results of the same studies and the present RCT confirm the gains of an early on discharge to be reflected in a pregnant reduction in the hospital stay of LBW babies without adversely affecting either the chances of survival or physical growth in the early months of life. Thus, the policy of early infirmary belch tin can be routinely practiced.

Conflict of involvement

The authors declare no disharmonize of involvement.

References

-

Stevan JG, Terri AS . Feeding the low birth weight babe. Clin Perinatol 1993; 20: 193–209.

-

Lang S, Lawrence CJ, L'E Orme R . Cup feeding: an alternative method of infant feeding. Curvation Dis Child 1994; 71: 365–369.

-

Malhotra N, Vishwambaram L, Indiranarayan KRS . A controlled trial of alternative method of oral feeding in neonates. Early on Hum Dev 1999; 54: 29–38.

-

Gupta A, Khanna G, Chatterjee S . Cup feeding: an alternative to bottle feeding in a neonatal intensive care unit. J Trop Pediatr 1999; 45: 108–110.

-

Marinelli KA, Burke GS, Dodd VL . A combination of prophylactic of loving cup feedings and bottle feedings in premature infants whose mothers intend to chest feed. J Perinatol 2001; 21: 350–355.

-

Seeley WG, Ellis RE, Flack FC, Brooks WA . Coordination of sucking, swallowing and breathing in the newborn: its relationship to baby feeding and normal development. Disord Commun 1990; 25: 311–327.

-

Dillard RG, Kononer CB . Lower belch weight and shortened nursery stay of low nascence weight infants. New Engl J Med 1973; 288: 131–133.

-

Hallam H . Standing care of the high risk infant. Clin Perinatol 1984; 11: 3–17.

-

Schmidt RE, Levine DH . Early on discharge of low birth weight infants equally a hospital policy. J Perinatol 1990; 10: 396–398.

-

Berg RB, Salisbury AJ . Discharging infants of depression birth weight: reconsideration of electric current practise. Am J Dis Child 1971; 122: 414–417.

-

Casiro OG, McKenzie ME, McFadyen 50, Shapiro C, Seshia MM, MacDonald N et al. Earlier belch with community based intervention for low nativity weight infants: randomized trial. Pediatrics 1993; 92: 128–134.

-

Cruz H, Guzman N, Rosales Thousand, Bastidas J, Garcia J, Hurtado I et al. Early hospital belch of preterm very low birth weight infants. J Perinatol 1997; 17: 29–32.

-

Gibson East, Medoff Cooper B, Nuamab IF, Gerdes J, Kirkby South, Greenspan J . Accelerated discharge of low nascence weight infants from neonatal intensive care. A randomized, controlled trial. J Perinatol 1998; 19: S17–S23.

-

Brooten D, Kumar S, Dark-brown 50, Butts P, Finkler SA, Bakewell-Sachs South et al. A randomized clinical trial of early infirmary discharge and home follow up of very depression birth weight infants. N Engl J Med 1986; 315: 934–939.

-

Kuppuswamy scale for socio-economic condition in urban surface area (1994) Source: Kuppuswamy B. Manual of socio-economic status calibration (URBAN) Manasayan 32 Netaji Shubhash Nagar, Delhi-110 006.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the advice of Professor Siddarth Ramji provided in the day-to-day direction of newborns during the study period and the statistical advice of Dr L Satyanarayana.

Writer information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kumar, A., Dabas, P. & Singh, B. Spoon feeding results in early hospital belch of low birth weight babies. J Perinatol thirty, 209–217 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2009.125

-

Received:

-

Revised:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

Issue Date:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2009.125

Keywords

- early hospital discharge

- feeding method

- domicile-based treatment

- LBW babies

- spoon feeding

Further reading

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/jp2009125

0 Response to "Clinical Trial Named Support Involving 1,300 Premature Babies"

Post a Comment