What Art Movement Was Happening After World War One in Italy

Futurism (Italian: Futurismo) was an creative and social movement that originated in Italy in the early 20th century and to a lesser extent in other countries. It emphasized dynamism, speed, applied science, youth, violence, and objects such as the auto, the airplane, and the industrial metropolis. Its key figures included the Italians Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Fortunato Depero, Gino Severini, Giacomo Balla, and Luigi Russolo. Italian Futurism glorified modernity and according to its doctrine, aimed to liberate Italy from the weight of its by.[one] Of import Futurist works included Marinetti'south 1909 Manifesto of Futurism, Boccioni's 1913 sculpture Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, Balla's 1913–1914 painting Abstruse Speed + Sound, and Russolo'due south The Art of Noises (1913).

Although Futurism was largely an Italian phenomenon, parallel movements emerged in Russia, where some Russian Futurists would afterward go on to found groups of their ain; other countries either had a few Futurists or had movements inspired by Futurism. The Futurists skillful in every medium of fine art, including painting, sculpture, ceramics, graphic design, industrial pattern, interior blueprint, urban design, theatre, film, fashion, textiles, literature, music, compages, and even cooking.

To some extent Futurism influenced the art movements Fine art Deco, Constructivism, Surrealism, and Dada, and to a greater degree Precisionism, Rayonism, and Vorticism. Passéism can represent an opposing trend or attitude.[ii]

Italian Futurism [edit]

Umberto Boccioni, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913)

Futurism is an avant-garde movement founded in Milan in 1909 by the Italian poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti.[1] Marinetti launched the movement in his Manifesto of Futurism,[3] which he published for the first fourth dimension on five February 1909 in La gazzetta dell'Emilia, an commodity then reproduced in the French daily newspaper Le Figaro on Sat 20 February 1909.[iv] [5] [6] He was shortly joined past the painters Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Giacomo Balla, Gino Severini and the composer Luigi Russolo. Marinetti expressed a passionate loathing of everything erstwhile, especially political and creative tradition. "We want no part of information technology, the past", he wrote, "nosotros the young and strong Futurists!" The Futurists admired speed, technology, youth and violence, the automobile, the airplane and the industrial city, all that represented the technological triumph of humanity over nature, and they were passionate nationalists. They repudiated the cult of the past and all faux, praised originality, "withal daring, however violent", bore proudly "the smear of madness", dismissed fine art critics equally useless, rebelled against harmony and skilful taste, swept away all the themes and subjects of all previous art, and gloried in science.

Publishing manifestos was a feature of Futurism, and the Futurists (usually led or prompted by Marinetti) wrote them on many topics, including painting, architecture, music, literature, photography, organized religion, women, mode and cuisine.[7] [viii]

The founding manifesto did non contain a positive artistic plan, which the Futurists attempted to create in their subsequent Technical Manifesto of Futurist Painting (published in Italian as a leaflet by Poesia, Milan, 11 April 1910).[9] This committed them to a "universal dynamism", which was to be directly represented in painting. Objects in reality were non separate from one another or from their surroundings: "The xvi people around you in a rolling motor double-decker are in turn and at the same fourth dimension one, ten four three; they are motionless and they alter places. ... The motor bus rushes into the houses which it passes, and in their plough the houses throw themselves upon the motor bus and are blended with it."[10]

The Futurist painters were slow to develop a distinctive mode and subject field matter. In 1910 and 1911 they used the techniques of Divisionism, breaking light and color down into a field of stippled dots and stripes, which had been adopted from Divisionism by Giovanni Segantini and others. Afterward, Severini, who lived in Paris, attributed their backwardness in mode and method at this time to their altitude from Paris, the centre of avant-garde art.[11] Cubism contributed to the germination of Italian Futurism's artistic style.[12] Severini was the first to come up into contact with Cubism and following a visit to Paris in 1911 the Futurist painters adopted the methods of the Cubists. Cubism offered them a ways of analysing free energy in paintings and expressing dynamism.

They ofttimes painted mod urban scenes. Carrà'south Funeral of the Anarchist Galli (1910–xi) is a large canvas representing events that the creative person had himself been involved in, in 1904. The activity of a police force attack and riot is rendered energetically with diagonals and broken planes. His Leaving the Theatre (1910–xi) uses a Divisionist technique to render isolated and faceless figures trudging home at night under street lights.

Boccioni's The Metropolis Rises (1910) represents scenes of construction and manual labour with a huge, rearing red horse in the centre foreground, which workmen struggle to control. His States of Mind, in 3 large panels, The Farewell, Those who Get, and Those Who Stay, "made his first great statement of Futurist painting, bringing his interests in Bergson, Cubism and the individual's circuitous experience of the mod world together in what has been described as one of the 'minor masterpieces' of early twentieth century painting."[13] The piece of work attempts to convey feelings and sensations experienced in time, using new means of expression, including "lines of force", which were intended to convey the directional tendencies of objects through space, "simultaneity", which combined memories, present impressions and anticipation of future events, and "emotional ambience" in which the artist seeks by intuition to link sympathies between the outside scene and interior emotion.[xiii]

Boccioni'due south intentions in fine art were strongly influenced by the ideas of Bergson, including the thought of intuition, which Bergson defined equally a simple, indivisible feel of sympathy through which one is moved into the inner existence of an object to grasp what is unique and ineffable inside it. The Futurists aimed through their art thus to enable the viewer to apprehend the inner existence of what they depicted. Boccioni developed these ideas at length in his book, Pittura scultura Futuriste: Dinamismo plastico (Futurist Painting Sculpture: Plastic Dynamism) (1914).[14]

Balla's Dynamism of a Canis familiaris on a Ternion (1912) exemplifies the Futurists' insistence that the perceived globe is in constant move. The painting depicts a domestic dog whose legs, tail and leash—and the feet of the adult female walking information technology—take been multiplied to a blur of movement. It illustrates the precepts of the Technical Manifesto of Futurist Painting that, "On business relationship of the persistency of an epitome upon the retina, moving objects constantly multiply themselves; their grade changes like rapid vibrations, in their mad career. Thus a running equus caballus has not four legs, but 20, and their movements are triangular."[ten] His Rhythm of the Bow (1912) similarly depicts the movements of a violinist'south paw and instrument, rendered in rapid strokes within a triangular frame.

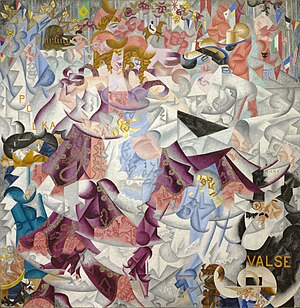

The adoption of Cubism determined the style of much subsequent Futurist painting, which Boccioni and Severini in particular continued to render in the cleaved colors and short brush-strokes of divisionism. Just Futurist painting differed in both subject matter and treatment from the placidity and static Cubism of Picasso, Braque and Gris. As the fine art critic Robert Hughes observed, "In Futurism, the center is fixed and the object moves, simply information technology is still the bones vocabulary of Cubism—fragmented and overlapping planes".[fifteen] While there were Futurist portraits: Carrà'southward Woman with Absinthe (1911), Severini'south Self-Portrait (1912), and Boccioni's Matter (1912), it was the urban scene and vehicles in motion that typified Futurist painting; Boccioni'due south The Street Enters the House (1911), Severini's Dynamic Hieroglyph of the Bal Tabarin (1912), and Russolo'due south Auto at Speed (1913)

The Futurists held their first exhibition outside of Italy in 1912 at the Bernheim-Jeune gallery, Paris, which included works by Umberto Boccioni, Gino Severini, Carlo Carrà, Luigi Russolo and Giacomo Balla.[16] [17]

In 1912 and 1913, Boccioni turned to sculpture to translate into three dimensions his Futurist ideas. In Unique Forms of Continuity in Infinite (1913) he attempted to realise the relationship between the object and its environment, which was central to his theory of "dynamism". The sculpture represents a striding figure, cast in statuary posthumously and exhibited in the Tate Modern. (It now appears on the national side of Italian 20 eurocent coins). He explored the theme further in Synthesis of Human Dynamism (1912), Speeding Muscles (1913) and Screw Expansion of Speeding Muscles (1913). His ideas on sculpture were published in the Technical Manifesto of Futurist Sculpture [18] In 1915 Balla too turned to sculpture making abstruse "reconstructions", which were created out of various materials, were apparently moveable and even made noises. He said that, afterward making twenty pictures in which he had studied the velocity of automobiles, he understood that "the single aeroplane of the canvas did non permit the proposition of the dynamic volume of speed in depth ... I felt the need to construct the outset dynamic plastic complex with iron wires, cardboard planes, cloth and tissue paper, etc."[19]

In 1914, personal quarrels and artistic differences between the Milan grouping, around Marinetti, Boccioni, and Balla, and the Florence group, around Carrà, Ardengo Soffici (1879–1964) and Giovanni Papini (1881–1956), created a rift in Italian Futurism. The Florence group resented the dominance of Marinetti and Boccioni, whom they accused of trying to found "an immobile church with an infallible creed", and each group dismissed the other as passéiste.

Futurism had from the outset admired violence and was intensely patriotic. The Futurist Manifesto had alleged, "We will glorify war—the world'due south simply hygiene—militarism, patriotism, the subversive gesture of freedom-bringers, beautiful ideas worth dying for, and contemptuousness for adult female."[6] [20] Although it owed much of its character and some of its ideas to radical political movements, it was not much involved in politics until the autumn of 1913.[xix] Then, fearing the re-election of Giolitti, Marinetti published a political manifesto. In 1914 the Futurists began to entrada actively against the Austria-hungary, which still controlled some Italian territories, and Italian neutrality between the major powers. In September, Boccioni, seated in the balcony of the Teatro dal Verme in Milan, tore upward an Austrian flag and threw it into the audience, while Marinetti waved an Italian flag. When Italian republic entered the First World War in 1915, many Futurists enlisted.[21] The experience of the war marked several Futurists, especially Marinetti, who fought in the mountains of Trentino at the border of Italy and Austria-Hungary, actively engaging in propaganda.[22] The combat experience too influenced Futurist music.[23]

The outbreak of state of war bearded the fact that Italian Futurism had come up to an end. The Florence group had formally acknowledged their withdrawal from the motion by the end of 1914. Boccioni produced only one state of war picture and was killed in 1916. Severini painted some significant state of war pictures in 1915 (e.g. War, Armored Train, and Ruby-red Cantankerous Train), simply in Paris turned towards Cubism and post-state of war was associated with the Render to Gild.

After the war, Marinetti revived the movement. This revival was called il secondo Futurismo (2nd Futurism) by writers in the 1960s. The art historian Giovanni Lista has classified Futurism by decades: "Plastic Dynamism" for the first decade, "Mechanical Art" for the 1920s, "Aeroaesthetics" for the 1930s.

Russian Futurism [edit]

Russian Futurism was a move of literature and the visual arts, involving various Futurist groups. The poet Vladimir Mayakovsky was a prominent member of the movement, as were Velimir Khlebnikov and Aleksei Kruchyonykh; visual artists such as David Burliuk, Mikhail Larionov, Natalia Goncharova, Lyubov Popova, and Kazimir Malevich found inspiration in the imagery of Futurist writings, and were writers themselves. Poets and painters collaborated on theatre production such as the Futurist opera Victory Over the Dominicus, with texts by Kruchenykh, music by Mikhail Matyushin, and sets by Malevich.

The chief style of painting was Cubo-Futurism, extant during the 1910s. Cubo-Futurism combines the forms of Cubism with the Futurist representation of movement; like their Italian contemporaries, the Russian Futurists were fascinated with dynamism, speed and the restlessness of modern urban life.

The Russian Futurists sought controversy by repudiating the art of the by, saying that Pushkin and Dostoevsky should be "heaved overboard from the steamship of modernity". They acknowledged no authorization and professed non to owe anything even to Marinetti, whose principles they had earlier adopted, most of whom obstructed him when he came to Russian federation to proselytize in 1914.

The motion began to decline after the revolution of 1917. The Futurists either stayed, were persecuted, or left the country. Popova, Mayakovsky and Malevich became part of the Soviet establishment and the cursory Agitprop movement of the 1920s; Popova died of a fever, Malevich would be briefly imprisoned and forced to paint in the new state-approved mode, and Mayakovsky committed suicide on April 14, 1930.

Architecture [edit]

The Futurist architect Antonio Sant'Elia expressed his ideas of modernity in his drawings for La Città Nuova (The New Metropolis) (1912–1914). This project was never built and Sant'Elia was killed in the First World War, but his ideas influenced subsequently generations of architects and artists. The city was a backdrop onto which the dynamism of Futurist life is projected. The metropolis had replaced the landscape as the setting for the exciting modern life. Sant'Elia aimed to create a city as an efficient, fast-paced auto. He manipulates light and shape to emphasize the sculptural quality of his projects. Baroque curves and encrustations had been stripped away to reveal the essential lines of forms unprecedented from their simplicity. In the new city, every aspect of life was to be rationalized and centralized into ane great powerhouse of energy. The metropolis was non meant to terminal, and each subsequent generation was expected to build their own metropolis rather than inheriting the architecture of the by.

Futurist architects were sometimes at odds with the Fascist land's trend towards Roman imperial-classical aesthetic patterns. Nevertheless, several Futurist buildings were built in the years 1920–1940, including public buildings such as railway stations, maritime resorts and mail service offices. Examples of Futurist buildings however in apply today are Trento railway station, congenital by Angiolo Mazzoni, and the Santa Maria Novella station in Florence. The Florence station was designed in 1932 by the Gruppo Toscano (Tuscan Group) of architects, which included Giovanni Michelucci and Italo Gamberini, with contributions past Mazzoni.

Music [edit]

Futurist music rejected tradition and introduced experimental sounds inspired by machinery, and would influence several 20th-century composers.

Francesco Balilla Pratella joined the Futurist motion in 1910 and wrote a Manifesto of Futurist Musicians in which he appealed to the young (as had Marinetti), because only they could understand what he had to say. According to Pratella, Italian music was inferior to music away. He praised the "sublime genius" of Wagner and saw some value in the work of other contemporary composers, for instance Richard Strauss, Elgar, Mussorgsky, and Sibelius. By contrast, the Italian symphony was dominated past opera in an "cool and anti-musical class". The conservatories was said to encourage backwardness and mediocrity. The publishers perpetuated mediocrity and the domination of music by the "rickety and vulgar" operas of Puccini and Umberto Giordano. The only Italian Pratella could praise was his instructor Pietro Mascagni, considering he had rebelled against the publishers and attempted innovation in opera, just fifty-fifty Mascagni was too traditional for Pratella's tastes. In the face up of this mediocrity and conservatism, Pratella unfurled "the red flag of Futurism, calling to its flaming symbol such young composers every bit have hearts to love and fight, minds to conceive, and brows free of cowardice."

Luigi Russolo (1885–1947) wrote The Art of Noises (1913),[24] [25] an influential text in 20th-century musical aesthetics. Russolo used instruments he called intonarumori, which were acoustic noise generators that permitted the performer to create and command the dynamics and pitch of several unlike types of noises. Russolo and Marinetti gave the first concert of Futurist music, consummate with intonarumori, in 1914. Even so they were prevented from performing in many major European cities by the outbreak of war.

Futurism was one of several 20th-century movements in art music that paid homage to, included or imitated machines. Ferruccio Busoni has been seen every bit anticipating some Futurist ideas, though he remained wedded to tradition.[26] Russolo'due south intonarumori influenced Stravinsky, Arthur Honegger, George Antheil, Edgar Varèse,[13] Stockhausen and John Muzzle. In Pacific 231, Honegger imitated the audio of a steam locomotive. There are too Futurist elements in Prokofiev'southward The Steel Step and in his 2d Symphony.

Near notable in this respect, however, is the American George Antheil. His fascination with machinery is axiomatic in his Airplane Sonata, Decease of the Machines, and the 30-minute Ballet Mécanique. The Ballet Mécanique was originally intended to accompany an experimental film past Fernand Léger, only the musical score is twice the length of the film and now stands alone. The score calls for a percussion ensemble consisting of three xylophones, four bass drums, a tam-tam, three airplane propellers, 7 electric bells, a siren, two "live pianists", and sixteen synchronized player pianos. Antheil'due south piece was the get-go to synchronize machines with human players and to exploit the difference between what machines and humans can play.

Dance [edit]

The Futuristic motility besides influenced the concept of dance. Indeed, dancing was interpreted as an alternative way of expressing man's ultimate fusion with the machine. The altitude of a flying aeroplane, the power of a car's motor and the roaring loud sounds of complex machinery were all signs of man'southward intelligence and excellence which the art of dance had to emphasize and praise. This type of dance is considered futuristic since it disrupts the referential system of traditional, classical dance and introduces a dissimilar fashion, new to the sophisticated bourgeois audience. The dancer no longer performs a story, a clear content, that can be read co-ordinate to the rules of ballet. One of the about famous futuristic dancers was the Italian Giannina Censi. Trained equally a classical ballerina, she is known for her "Aerodanze" and continued to earn her living by performing in classical and popular productions. She describes this innovative form of dance as the event of a deep collaboration with Marinetti and his poetry. Through these words, she says,

I launched this idea of the aeriform-futurist poetry with Marinetti, he himself declaiming the poesy. A minor stage of a few square meters;... I fabricated myself a satin costume with a helmet; everything that the plane did had to be expressed by my torso. It flew and, moreover, information technology gave the impression of these wings that trembled, of the appliance that trembled, ... And the confront had to express what the pilot felt."[27] [28]

Literature [edit]

Futurism as a literary motion made its official debut with F. T. Marinetti's Manifesto of Futurism (1909), equally it delineated the various ideals Futurist poetry should strive for. Verse, the predominant medium of Futurist literature, tin can be characterized by its unexpected combinations of images and hyper-conciseness (non to be confused with the bodily length of the poem). The Futurists called their style of poetry parole in libertà (give-and-take autonomy), in which all ideas of meter were rejected and the give-and-take became the primary unit of business. In this fashion, the Futurists managed to create a new language free of syntax punctuation, and metrics that allowed for free expression.

Theater also has an important place within the Futurist universe. Works in this genre have scenes that are few sentences long, have an emphasis on nonsensical humor, and attempt to discredit the deep rooted traditions via parody and other devaluation techniques.

There are a number of examples of Futurist novels from both the initial period of Futurism and the neo-Futurist flow, from Marinetti himself to a number of bottom known Futurists, such as Primo Conti, Ardengo Soffici and Giordano Bruno Sanzin (Zig Zag, Il Romanzo Futurista edited by Alessandro Masi, 1995). They are very diverse in style, with very little recourse to the characteristics of Futurist Poetry, such every bit 'parole in libertà'. Arnaldo Ginna's 'Le locomotive con le calze' (Trains with socks on) plunges into a world of absurd nonsense, childishly rough. His brother Bruno Corra wrote in Sam Dunn è morto (Sam Dunn is Dead) a masterpiece of Futurist fiction, in a genre he himself chosen 'Synthetic' characterized by pinch, and precision; it is a sophisticated slice that rises above the other novels through the strength and pervasiveness of its irony. Science fiction novels play an important office in Futurist literature.[29]

Film [edit]

When interviewed nigh her favorite film of all times,[30] famed moving picture critic Pauline Kael stated that the director Dimitri Kirsanoff, in his silent experimental film Ménilmontant "developed a technique that suggests the movement known in painting every bit Futurism".[31]

Thaïs ("Thaïs"), directed by Anton Giulio Bragaglia (1917), is the only surviving of the 1910s Italian futurist cinema to date (35 min. of the original 70 min.).[32]

Female Futurists [edit]

Within F. T. Marinetti's The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism, two of his tenets briefly highlight his hatred for women under the pretense that information technology fuels the Futurist motility's visceral nature:

9. Nosotros intend to glorify state of war—the only hygiene of the earth—militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of anarchists, beautiful ideas worth dying for, and contempt for adult female.

ten. We intend to destroy museums, libraries, academics of every sort and to fight against moralism, feminism, and every commonsensical opportunistic cowardice.[3]

Marinetti would brainstorm to contradict himself when, in 1911, he called Luisa, Marchesa Casati a Futurist; he dedicated a portrait of himself painted past Carrà to her, the said dedication declaring Casati as a Futurist being pasted on the canvas itself.[33]

In 1912, only 3 years subsequently the Manifesto of Futurism was published, Valentine de Saint-Bespeak responded to Marinetti's claims in her Manifesto of the Futurist Woman (Response to F. T. Marinetti). Marinetti even subsequently referred to her as "the 'first futurist woman.'"[34] Her manifesto begins with a misanthropic tone past presenting how men and women are equal and both deserve contempt.[35] She instead suggests that rather than the binary being limited to men and women, it should exist replaced with "femininity and masculinity"; ample cultures and individuals should possess elements of both.[35] Yet, she still embraces the cadre values of Futurism, especially its focus on "virility" and "brutality". Saint-Point uses this as a segue into her antifeminist argument—giving women equal rights destroys their innate "potency" to strive for a better, more fulfilling life.[35]

In Russian Futurist and Cubo-Futurist circles, all the same, from the start, at that place was a college per centum of women participants than in Italian republic; examples of major female person Futurists are Natalia Goncharova, Aleksandra Ekster, and Lyubov Popova. Although Marinetti expressed his approval of Olga Rozanova'due south paintings during his 1914 lecture tour of Russia, information technology is possible that the women painters' negative reaction to the said tour may have largely been due to his misogyny.

Despite the antipathetic nature of the Italian Futurist plan, many serious professional female artists adopted the way, especially so after the end of the first World War. Notably amongst these female futurists is F.T Marinetti's own married woman Benedetta Cappa Marinetti, whom he had met in 1918 and exchanged a series of letters discussing each of their respective piece of work in Futurism. Letters connected to be exchanged between the ii with F. T. Marinetti often complimenting Benedetta – the single proper noun she was all-time known as – on her genius. In a letter dated August 16, 1919, Marinetti wrote to Benedetta "Do not forget your hope to piece of work. You must carry your genius to its ultimate splendor. Every day."[36] Although many of Benedetta's paintings were exhibited in major Italian exhibitions like the 1930-1936 Venice Biennales (in which she was the first woman to have her art displayed since the exhibition's founding in 1895[37]), the 1935 Rome Quadriennale and several other futurist exhibitions, she was oft overshadowed in her work by her married man. The first introduction of Benedetta's feminist convictions regarding futurism is in the form of a public dialogue in 1925 (with an 50. R. Cannonieri) concerning the part of women in order.[37] Benedetta was also i of the first to paint in Aeropittura, an abstract and futurist art mode of mural from the view of an airplane.

1920s and 1930s [edit]

Many Italian Futurists supported Fascism in the hope of modernizing a country divided between the industrialising north and the rural, primitive South. Similar the Fascists, the Futurists were Italian nationalists, laborers, disgruntled war veterans, radicals, admirers of violence, and were opposed to parliamentary commonwealth. Marinetti founded the Futurist Political Party (Partito Pol Futurista) in early 1918, which was captivated into Benito Mussolini'south Fasci Italiani di Combattimento in 1919, making Marinetti one of the beginning members of the National Fascist Party. He opposed Fascism'due south afterward exaltation of existing institutions, calling them "reactionary", and walked out of the 1920 Fascist political party congress in disgust, withdrawing from politics for three years; merely he supported Italian Fascism until his decease in 1944. The Futurists' association with Fascism after its triumph in 1922 brought them official acceptance in Italy and the power to bear out important work, especially in compages. Later the 2nd World State of war, many Futurist artists had difficulty in their careers because of their association with a defeated and discredited government.

Marinetti sought to make Futurism the official state art of Fascist Italy simply failed to do so. Mussolini chose to give patronage to numerous styles and movements in order to go along artists loyal to the government. Opening the exhibition of art by the Novecento Italiano group in 1923, he said, "I declare that it is far from my thought to encourage anything like a state fine art. Fine art belongs to the domain of the individual. The state has only one duty: not to undermine fine art, to provide humane atmospheric condition for artists, to encourage them from the artistic and national point of view."[38] Mussolini's mistress, Margherita Sarfatti, who was as able a cultural entrepreneur every bit Marinetti, successfully promoted the rival Novecento group, and even persuaded Marinetti to sit on its board. Although in the early years of Italian Fascism modern fine art was tolerated and fifty-fifty embraced, towards the finish of the 1930s, correct-wing Fascists introduced the concept of "degenerate art" from Federal republic of germany to Italy and condemned Futurism.

Marinetti made numerous moves to ingratiate himself with the regime, becoming less radical and avant-garde with each. He moved from Milan to Rome to be nearer the centre of things. He became an academician despite his condemnation of academies, married despite his condemnation of marriage, promoted religious art after the Lateran Treaty of 1929 and even reconciled himself to the Catholic Church, declaring that Jesus was a Futurist.

An instance of Futurist design: "Skyscraper Lamp", past the Italian architect Arnaldo dell'Ira, 1929

Although Futurism mostly became identified with Fascism, it had a diverse range of supporters. They tended to oppose Marinetti's creative and political management of the move, and in 1924 the socialists, communists and anarchists walked out of the Milan Futurist Congress. The anti-Fascist voices in Futurism were not completely silenced until the looting of Abyssinia and the Italo-High german Pact of Steel in 1939.[39] This clan of Fascists, socialists and anarchists in the Futurist movement, which may seem odd today, can exist understood in terms of the influence of Georges Sorel, whose ideas near the regenerative effect of political violence had adherents right across the political spectrum.

Aeropainting [edit]

Aeropainting (aeropittura) was a major expression of the second generation of Futurism beginning in 1926. The engineering and excitement of flight, directly experienced past most aeropainters,[40] offered aeroplanes and aeriform landscape as new subject thing. Aeropainting was varied in bailiwick thing and treatment, including realism (especially in works of propaganda), abstraction, dynamism, quiet Umbrian landscapes,[41] portraits of Mussolini (e.g. Dottori's Portrait of il Duce), devotional religious paintings, decorative art, and pictures of planes.

Aeropainting was launched in a manifesto of 1929, Perspectives of Flight, signed by Benedetta, Depero, Dottori, Fillìa, Marinetti, Prampolini, Somenzi and Tato (Guglielmo Sansoni). The artists stated that "The changing perspectives of flight constitute an absolutely new reality that has nothing in common with the reality traditionally constituted past a terrestrial perspective" and that "Painting from this new reality requires a profound contempt for detail and a need to synthesise and transfigure everything." Crispolti identifies 3 principal "positions" in aeropainting: "a vision of catholic projection, at its nearly typical in Prampolini's 'catholic idealism' ... ; a 'reverie' of aerial fantasies sometimes verging on fairy-tale (for example in Dottori ...); and a kind of aeronautical documentarism that comes dizzyingly close to direct celebration of mechanism (particularly in Crali, just also in Tato and Ambrosi)."[42]

Somewhen there were over a hundred aeropainters. Major figures include Fortunato Depero, Marisa Mori, Enrico Prampolini, Gerardo Dottori, Mino Delle Site and Crali. Crali continued to produce aeropittura up until the 1980s.

Legacy [edit]

Futurism influenced many other twentieth-century art movements, including Fine art Deco, Vorticism, Constructivism, Surrealism, Dada, and much afterward Neo-Futurism[43] [44] and the Grosvenor School linocut artists.[45] Futurism as a coherent and organized artistic movement is now regarded as extinct, having died out in 1944 with the death of its leader Marinetti.

Nevertheless, the ideals of Futurism remain as meaning components of modern Western culture; the emphasis on youth, speed, power and applied science finding expression in much of modern commercial cinema and culture. Ridley Scott consciously evoked the designs of Sant'Elia in Blade Runner. Echoes of Marinetti'south thought, particularly his "dreamt-of metallization of the man trunk", are still strongly prevalent in Japanese culture, and surface in manga/anime and the works of artists such as Shinya Tsukamoto, managing director of the Tetsuo (lit. "Ironman") films. Futurism has produced several reactions, including the literary genre of cyberpunk—in which engineering science was frequently treated with a critical eye—whilst artists who came to prominence during the get-go flush of the Internet, such as Stelarc and Mariko Mori, produce work which comments on Futurist ideals. and the art and architecture movement Neo-Futurism in which technology is considered a driver to a amend quality of life and sustainability values.[46] [47]

A revival of sorts of the Futurist move in theatre began in 1988 with the creation of the Neo-Futurist fashion in Chicago, which utilizes Futurism's focus on speed and brevity to create a new form of immediate theatre. Currently, at that place are active Neo-Futurist troupes in Chicago, New York, San Francisco, and Montreal.[48]

Futurist ideas take been a major influence in Western pop music; examples include ZTT Records, named after Marinetti'south verse form Zang Tumb Tumb; the band Art of Racket, named later on Russolo's manifesto The Fine art of Noises; and the Adam and the Ants single "Zerox", the encompass featuring a photograph by Bragaglia. Influences can as well exist discerned in trip the light fantastic toe music since the 1980s.[49]

Japanese Composer Ryuichi Sakamoto's 1986 album "Futurista" was inspired past the movement. It features a speech from Tommaso Marinetti in the track 'Variety Evidence'.[l]

In 2009, Italian director Marco Bellocchio included Futurist art in his characteristic film Vincere.[51]

In 2014, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum featured the exhibition "Italian Futurism, 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe".[52] This was the first comprehensive overview of Italian Futurism to be presented in the United States.[53]

Estorick Collection of Mod Italian Fine art is a museum in London, with a collection solely centered effectually modern Italian artists and their works. It is all-time known for its big collection of Futurist paintings.

Futurism, Cubism, press articles and reviews [edit]

-

Photos, in descending social club: Carlo Carrà, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Umberto Boccioni, Luigi Russolo. Paintings, in descending order: Luigi Russolo, 1911, Souvenir d'united nations nuit, 1911–12, La révolte (ii versions are depicted here); Umberto Boccioni, 1912, Le rire; Gino Severini, 1911, La danseuse obsedante. Published in The Sun, 25 February 1912

-

Paintings by Gino Severini, 1911, La Danse du Pan-Pan, and Severini, 1913, L'autobus. Published in Les Annales politiques et littéraires, Le Paradoxe Cubiste, 14 March 1920

-

Paintings by Gino Severini, 1911, Souvenirs de Voyage; Albert Gleizes, 1912, Man on a Balcony, Fifty'Homme au balcon; Severini, 1912–13, Portrait de Mlle Jeanne Paul-Fort; Luigi Russolo, 1911–12, La Révolte. Published in Les Annales politiques et littéraires, Le Paradoxe Cubiste (continued), n. 1916, 14 March 1920

People involved with Futurism [edit]

This is a partial list of people involved with the Futurist motility.

Architects [edit]

- Angiolo Mazzoni, Italian architect

- Antonio Sant'Elia, Italian architect

Actors and dancers [edit]

- Arturo Bragaglia, Italian actor

- Giannina Censi, dancer

Artists [edit]

- Giacomo Balla, Italian painter and playwright[54]

- Alice Bailly, Swiss painter

- Umberto Boccioni, Italian painter and sculptor

- Alexander Bogomazov, Ukrainian painter

- Kseniya Boguslavskaya, Russian painter

- Anton Giulio Bragaglia, Italian artist and photographer

- David Burliuk, Ukrainian painter and co-founder of Russian Futurism

- Vladimir Burliuk, Ukrainian painter and co-founder of Russian Futurism

- Francesco Cangiullo, Italian author and painter

- Benedetta Cappa, Italian painter and author

- Carlo Carrà, Italian painter

- Ambrogio Casati, Italian painter

- Primo Conti, Italian creative person

- Tullio Crali, Italian artist

- Luigi De Giudici, Italian painter

- Natalia Goncharova, Russian painter

- Fortunato Depero, Italian painter

- Gerardo Dottori, Italian painter, poet and art critic

- Aleksandra Ekster, Ukrainian painter and designer

- Fillìa, Italian artist

- Félix Del Marle, French painter

- Kazimir Malevich, Soviet and Ukrainian painter and developer of Cubo-Futurism

- Sante Monachesi, Italian painter

- Marisa Mori, Italian painter

- Almada Negreiros, Portuguese painter, poet and novelist

- C. R. West. Nevinson, English language painter and memoirist

- Mikhail Larionov, Russian painter

- Aristarkh Lentulov, Russian painter

- Aldo Palazzeschi, Italian writer

- Ivo Pannaggi, Italian artist

- Giovanni Papini, Italian writer

- Emilio Pettoruti, Argentinian painter

- Lyubov Popova, Russian painter

- Enrico Prampolini, Italian painter, sculptor and scenographer

- Ivan Puni, Russian painter

- Olga Rozanova, Russian painter

- Luigi Russolo, Italian painter, musician, instrument builder

- Jules Schmalzigaug, Belgian painter

- Gino Severini, Italian painter

- Ardengo Soffici, Italian painter and writer

- Joseph Stella, Italian-American painter

- Frances Simpson Stevens, American painter

- Mary Swanzy, Irish gaelic painter

- Růžena Zátková, Czech painter

Composers and musicians [edit]

- Aldo Giuntini, Italian composer

- Luigi Grandi, Italian composer

- Nikolai Kulbin, Russian musician

- Virgilio Mortari, Italian composer

- Francesco Balilla Pratella, Italian composer, musicologist and essayist

- Ugo Piatti, instrument maker, luthier and artist

- Luigi Russolo, Italian painter, musician, instrument architect

Writers and poets [edit]

- Giacomo Balla, Italian painter and playwright[54]

- Francesco Cangiullo, Italian writer and painter

- Benedetta Cappa, Italian painter and writer

- Mario Carli, Italian poet

- Gerardo Dottori, Italian painter, poet and art critic

- Escodamè (Michele Leskovic), Italian poet and artist

- Farfa, Italian poet

- Ilya Zdanevich ("Iliazd"), Georgian writer

- Bruno Jasieński, Polish poet, prosaist and playwright

- Velimir Khlebnikov, Russian poet

- Aleksei Kruchenykh, Russian poet

- Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Italian poet, playwright, novelist, journalist, theorist and founder of Futurism

- Vladimir Mayakovsky, Russian poet and playwright

- Almada Negreiros, Portuguese painter, poet and novelist

- C. R. West. Nevinson, English painter and memoirist

- Aldo Palazzeschi, Italian writer

- Giovanni Papini, Italian writer

- Mykhaylo Semenko, Ukrainian poet and founder of Panfuturism, founder of 'Nova Generatsia' (New Generation) futuristic magazine

- Igor Severyanin, Russian poet and leader of Ego-Futurism

- Ardengo Soffici, Italian painter and author

- Vincenzo Fani Ciotti, Italian novelist and political author

Scenographers [edit]

- Enrico Prampolini, Italian painter, sculptor and scenographer

See also [edit]

- Africanfuturism

- Afrofuturism

- Art manifesto

- Futurist cooking

- Googie architecture

- High-tech architecture

- Raygun Gothic

- Universal Flowering

- Indigenous Futurism

References [edit]

- ^ a b The 20th-Century art book (Reprinted. ed.). dsdLondon: Phaidon Printing. 2001. ISBN978-0714835426.

- ^ Shershenevich, Five. (2005) [1988]. "From Greenish Street". In Lawton, Anna; Eagle, Herbert (eds.). Words in Revolution: Russian Futurist Manifestoes, 1912–1928. Translated by Lawton, Anna; Eagle, Herbert. Washington, DC: New Academia Publishing, LLC. p. 153. ISBN9780974493473 . Retrieved 18 January 2022.

Italo-Futurism flees the shores of passéism because the tentacles of passéism are suffocating it; it is flying from captivity. Russian Futurism flees passéism like a homo who steps back in preparing to jump forward.

- ^ a b Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, I manifesti del futurismo, February 20, 2009

- ^ Le Figaro, Le Futurisme, 1909/02/20 (Numéro 51). Gallica, Bibliothèque nationale de France

- ^ Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Declaration of Futurism, published in Poesia, Book 5, Number six, April 1909 (Futurist manifesto translated to English). Blue Mountain Project

- ^ a b Futurist Manifesto, reproduced in Futurist Aristocracy, New York, April 1923

- ^ Umbro Apollonio (ed.), Futurist Manifestos, MFA Publications, 2001 ISBN 978-0-87846-627-half dozen

- ^ Jessica Palmieri, Futurist manifestos, 1909–1933, italianfuturism.org

- ^ I Manifesti del futurismo, lanciati da Marinetti, et al, 1914 (in Italian)

- ^ a b "Technical Manifesto of Futurist Painting". Unknown.nu. Retrieved 2011-06-11 .

- ^ Severini, G., The Life of a Painter, Princeton, Princeton University Printing, 1995. ISBN 0-691-04419-8

- ^ Arnason; Harvard, H.; Mansfield, Elizabeth (Dec 2012). History of Modernistic Art: Painting, Sculpture, Compages, Photography (7th ed.). Pearson. p. 189. ISBN978-0205259472.

- ^ a b c Humphreys, R. Futurism, Tate Gallery, 1999

- ^ For detailed discussions of Boccioni's debt to Bergson, encounter Petrie, Brian, "Boccioni and Bergson", The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 116, No.852, March 1974, pp.140-147, and Antliff, Mark "The 4th Dimension and Futurism: A Politicized Infinite", The Art Bulletin, December 2000, pp.720-733.

- ^ Hughes, Robert (1990). Nothing If Not Disquisitional. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 220. ISBN978-0-307-80959-nine.

- ^ Les Peintres futuristes italiens, Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, Paris, 5–24 February 1912

- ^ R. Bruce Elder, Cubism and Futurism: Spiritual Machines and the Cinematic Effect, Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press, 2018, ISBN 1771122722

- ^ "Technical Manifesto of Futurist Sculpture". Unknown.nu. 1910-04-11. Retrieved 2011-06-11 .

- ^ a b Martin, Marianne Due west. Futurist Art and Theory, Hacker Art Books, New York, 1978

- ^ "The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism". Unknown.nu. Retrieved 2011-06-11 .

- ^ Adler, Jerry, "Back to the Futurity", The New Yorker, September 6, 2004, p.103

- ^ Daly, Selena (2013-xi-01). "'The Futurist mountains': Filippo Tommaso Marinetti'southward experiences of mountain combat in the First World War". Modern Italia. 18 (4): 323–338. doi:10.1080/13532944.2013.806289. ISSN 1353-2944.

- ^ Daly, Selena (2013). "Futurist War Noises: Against and Coping with the First World State of war". California Italian Studies. 4. doi:10.5070/C341015976. Retrieved 2015-09-thirteen .

- ^ Russolo, Luigi (2004-02-22). "The Art of Noises on Theremin Vox". Thereminvox.com. Archived from the original on 2011-06-07. Retrieved 2011-06-11 .

- ^ The Art of Noises Archived September 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Daniele Lombardi in Futurism and Musical Notes". Ubu.com. Retrieved 2011-06-11 .

- ^ Klöck, A. (1999) "Of Cyborg Technologies and Fascistized Mermaids: Giannina Censi's 'Aerodanze' in 1930s Italy", Theatre Journal 51(4): 395–415

- ^ Juliet Blare, Futurism and Trip the light fantastic toe, Routledge Encyclopedia of Modernism, 305, American University, 09/05/2016

- ^ Brioni, Simone; Comberiati, Daniele (2019). Italian Science Fiction: The Other in Literature and Film. New York: Palgrave, 2019. ISBN9783030193263.

- ^ Barra, Allen (twenty November 2002). "Afterglow: A Last Conversation With Pauline Kael" by Francis Davis Archived 2009-01-20 at the Wayback Auto, Salon.com. Retrieved on 2008-10-nineteen

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "Pauline Kael'southward favorite film". Rogerebert.com . Retrieved thirteen January 2018.

- ^ 30 Essential Films for an Introduction to Italian Cinema « Taste of Picture palace

- ^ Dedication written past Marinetti, Filippo on Portrait of Marinetti (1911) by Carrá, Carlo and translated by Tisdall, Caroline and Bozzolla, Angelo in Futurism (Thames & Hudson; 1977; p. 156); "I give my portrait painted by Carrá to the great Futurist Marchesa Casati, to her languid jaguar's optics which digest in the sun the cage of steel which she has devoured."

- ^ Martens, David (Fall 2013). "The Aristocratic Avant-garde of Valentine de Saint-Indicate". Johns Hopkins Academy Press. 53: 1–iii. ProQuest 1462231304.

- ^ a b c de Saint-Point, Valentine (1912). Manifesto of the Futurist Adult female. Italy: Governing Group of the Futurist Movement. pp. 109–113.

- ^ Conaty, Siobhan One thousand. (2009). "Benedetta Cappa Marinetti and the Second Stage of Futurism". Adult female's Art Journal. 30 (1): 19–28. JSTOR 40605218.

- ^ a b Katz, K. Barry (1986). "The Women of Futurism". Woman'south Art Periodical. 7 (2): three–13. doi:10.2307/1358299. JSTOR 1358299.

- ^ Quoted in Braun, Emily, Mario Sironi and Italian Modernism: Art and Politics under Fascism, Cambridge University Press, 2000

- ^ Berghaus, Günther, "New Research on Futurism and its Relations with the Fascist Regime", Journal of Contemporary History, 2007, Vol. 42, p. 152

- ^ "Osborn, Bob, Tullio Crali: the Ultimate Futurist Aeropainter". Simultaneita.net. Archived from the original on 2010-02-07. Retrieved 2011-06-11 .

- ^ "... dal realismo esasperato e compiaciuto (in particolare delle opere propagandistiche) alle forme asatratte (come in Dottori: Trittico della velocità), dal dinamismo alle quieti lontane dei paesaggi umbri di Dottori ... ." 50'aeropittura futurista

- ^ Crispolti, Due east., "Aeropainting", in Hulten, P., Futurism and Futurisms, Thames and Hudson, 1986, p. 413

- ^ Hal Foster, Neo-Futurism. Published by: Architectural Clan School of Architecture

- ^ Karen Pinkus, Cocky-Representation in NeoFuturism and Punk. Published past: The Johns Hopkins Academy Press

- ^ Gordon, Samuel; Leaper, Hana; Lock, Tracey; Vann, Philip; Scott, Jennifer (2019-08-thirteen). Gordon, Samuel (ed.). Cutting Edge: Modernist British Printmaking (Exhibition Catalogue) (1st ed.). Philip Wilson Publishers. p. Inside front flap. ISBN978-1-78130-078-7.

- ^ Yes is More. An Archicomic on Architectural Evolution Retrieved 2014-01-23

- ^ Jean-Louis Cohen, The Time to come of Compages. Since 1889, London: Phaidon, 2012

- ^ Potter, Janet (xvi December 2013). "Too Much Light at 25: An oral history". Reader . Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- ^ At Society to Club Festival, Dance Music's Growing Embrace of Futurism Reigns. From Pitchfork; access date unknown

- ^ Ryuichi Sakamoto interview published Music Technology Magazine in August 1987

- ^ "MoMA | Finding The Robot". www.moma.org . Retrieved 2015-09-13 .

- ^ "Italian Futurism, 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe", Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

- ^ Guggenheim Museum's Italian Futurism Exhibition Archived July 6, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Angelo Bozzolla and Caroline Tisdall, Futurism, Thames & Hudson, p. 107

Further reading [edit]

- Coen, Ester (1988). Umberto Boccioni . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN9780870995224.

- Conversi, Daniele 2009 "Art, Nationalism and War: Political Futurism in Italian republic (1909–1944)", Sociology Compass, 3/1 (2009): 92–117.

- D'Orsi Angelo 2009 'Il Futurismo tra cultura eastward politica. Reazione o rivoluzione?'. Editore: Salerno

- Gentile, Emilo. 2003. The Struggle for Modernity: Nationalism, Futurism, and Fascism. Praeger Publishers. ISBN 0-275-97692-0

- I poeti futuristi, dir. past M. Albertazzi, due west. essay of G. Wallace and One thousand. Pieri, Trento, La Finestra editrice, 2004. ISBN 88-88097-82-1

- John Rodker (1927). The hereafter of futurism. New York: E.P. Dutton & company.

- Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi, and Laura Wittman, eds., Futurism: An Anthology (Yale, 2009). ISBN 9780300088755.

- Futurism & Sport Design, edited by M. Mancin, Montebelluna-Cornuda, Antiga Edizioni, 2006. ISBN 88-88997-29-half-dozen

- Manifesto of Futurist Musicians past Francesco Balilla Pratella

- Donatella Chiancone-Schneider (editor) "Zukunftsmusik oder Schnee von gestern? Interdisziplinarität, Internationalität und Aktualität des Futurismus", Cologne 2010 Congress papers

- Berghaus, Gunter, Futurism and the technological imagination, Rodopi, 2009 ISBN 978-9042027473

- Berghaus, Gunter, International Yearbook of Futurism Studies, De Gruyter.

- Zaccaria, Gino, The Enigma of Fine art: On the Provenance of Creative Creation, Brill, 2021 (https://brill.com/view/title/59609)

External links [edit]

| | Wikiquote has quotations related to: Futurism |

- Cycling, Cubo‐Futurism and the 4th Dimension. Jean Metzinger'southward "At the Bicycle‐Race Track", Curated by Erasmus Weddigen, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, 2012 Archived 2016-03-05 at the Wayback Machine

- Futurism: Manifestos and Other Resources

- The Futurist Moment: Howlers, Exploders, Crumplers, Hissers, and Scrapers past Kenneth Goldsmith

- Futurism: archive audio recordings at LTM

- Encyclopædia Britannica

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Futurism

0 Response to "What Art Movement Was Happening After World War One in Italy"

Post a Comment